We must first determine, what is a person and what is the nature of the universe in which a person can exist?

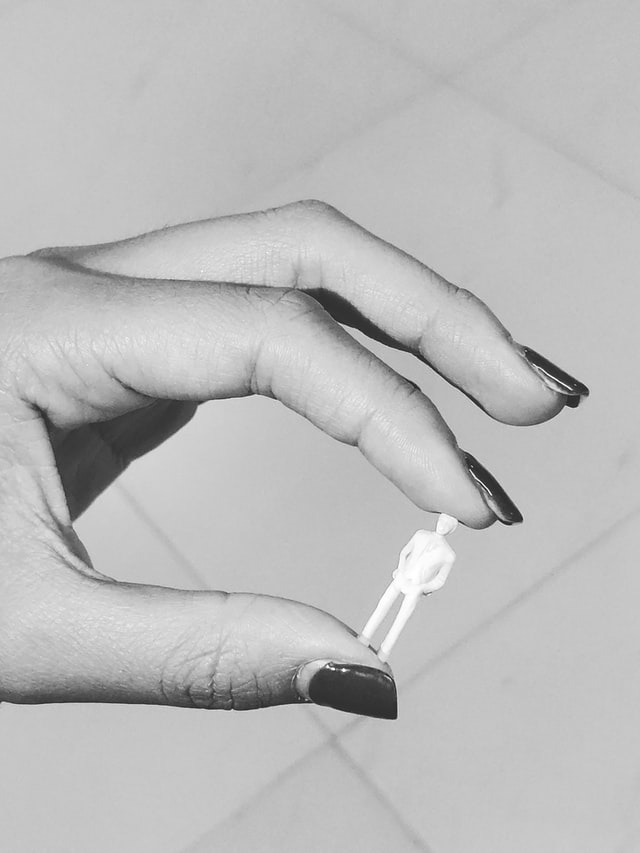

The title question has been around for quite some time. In this discussion, I would like to take an ontological look at this question. What is the essential nature of being a person? To fully replace humans, what must AI machines become capable of? IF we want to consider the possibility of making humans obsolete, we need to know what is the essence of humanity? What is the ontological nature of a person? What characteristics define being a person?

Even before we can address the essential nature of a person, we must identify the essential nature of the universe in which that person exists. What is the universe? How many dimensions does it have? Can the universe, or in it a person, be fully described by the four dimensions of space plus time? Does the universe (and the people in it) extend into other dimensions?

Separate from the dimensions of existence, we must explore what domains define human existence. In what domains is the uniqueness of humanity most clearly seen and most fully expressed? Almost all reflective people agree that our bodies, our physical existence, are one of the less important aspects of our being. Most would agree that character is a much more important expression of a person. But character does not exist in time and space. Character exists in a different dimension. Character cannot be defined by XYZ coordinates plus time.

Once we have answers to those questions, and know the full set of dimensions and domains of the universe and know what a human is, we can take on the question of whether AI can ever fully replace a human? Do humans have capabilities that a machine can never replicate?

What is the Universe?

Some have argued that all that exists is the material universe. This argument is sometimes clothed in the mantle of “science.” All that exists is what science can observe and measure. As we will see, however, that view conflicts with both modern physics and religion, and probably philosophy as well:

String theory is a purported theory of everything that physicists hope will one day explain … everything.

All the forces, all the particles, all the constants, all the things under a single theoretical roof, where everything that we see is the result of tiny, vibrating strings. Theorists have been working on the idea since the 1960s, and one of the first things they realized is that for the theory to work, there have to be more dimensions than the four we’re used to…

Current versions of string theory require 10 dimensions total, while an even more hypothetical über-string theory known as M-theory requires 11.”

PAUL SUTTER, “HOW THE UNIVERSE COULD POSSIBLY HAVE MORE DIMENSIONS” AT SPACE.COM (FEBRUARY 21, 2020)

So the best physicists working on this topic insist that our universe has at least ten dimensions, of which we can observe four.

We can call what we can directly observe with our unaided senses the “directly sensible” universe. Beyond the universe we can explore using our senses there is the universe we can observe using various instruments to extend or enhance our senses. However, are these observations really what best describes the universe? Does this best fit the facts we have?

We start with the universe that we can perceive with our senses. We know that much exists that we cannot see, hear, taste, touch, or smell. There is light above and below the visible spectrum. We cannot see this part of the light spectrum with our eyes. There are sounds outside the range that our ears can hear. There is a real universe that is much larger than the one we have direct access to by our senses. We can know a lot about the non-sensible universe through instruments that give us access. Sometimes we can deduce its presence by effects that we can directly observe.

The way we perceive the universe also depends on how well our senses work. Our senses are ultimately sensors that deliver information to our brain. If the sensor is not accurate, the brain will be getting distorted information. Our sensors are not perfect either. They have a variety of limits and imperfections. Many of us wear glasses to correct imperfections in our vision. Without our glasses our brains are given inaccurate information about the world. Our hearing is more sensitive to some sounds than others. Our brains may get the wrong idea about the sounds in our world if they don’t learn to adjust to that characteristic of our hearing. Our temperature sensitivity is more relative than absolute. The thermoreceptors in the human body respond to differences between the body’s temperature and the surface being touched. Further, these thermoreceptors are more active at first contact but signal less if left in contact for a time. We must accept that our brains deal with imperfect data because our biological sensors have both limited ranges but also have imperfections. Hence, there is the universe that our brains perceive and there is the actual universe, which is both larger and different from the one our senses tell us about.

Let’s now set aside what we can observe in the three spatial dimensions and think about time. We can only directly observe the present. The past and future are not directly observable. We can record the past. When we record the past using our brain, we call that memory. We can take pictures of things that happened in the past. We can deduce past events from things we observe in the present. However, we cannot directly observe the past.

Similarly, we cannot see the future. We can extrapolate trends into the future. We can predict the future with varying degrees of accuracy. But we cannot directly observe the future.

The past and the future are ideas, concepts, abstractions. Neither can be directly observed. If all that exists is what we can directly observe, then there is no past or future, only the present. In that view there is no reason to discuss whether AI can replace man because it doesn’t today. In this view, the future cannot be directly observed, it does not yet exist and so the question is irrelevant. However, for most of us, the past and future are very real. Most of us believe in learning from the past and planning for the future.

Up to this point, we can conclude that there is a universe beyond the one we can directly perceive that is much larger than the sensible universe. There are also past and future states of the universe. A man, as part of this universe, will then be more than what can be observed with our senses and will have a real past and future. To fully observe a human, we must not only enhance our senses with instruments, which our doctors regularly do, but bring in additional dimensions. We cannot fully “see” a person with our unaided senses nor can we get a full picture of a person without including the temporal past. As just one example, blood clots are often found using ultrasound and observing the direction of blood flow. If the blood flows “upstream” there is an obstruction, a blood clot in the vesicle. Direction of flow introduces another domain. Direction of blood flow cannot be observed in a single instant of time; it is a composite of where the blood is in the three spatial dimensions over time, the past up to the present.

We are now introducing more fully the concepts of dimensions and domains. A dimension is orthogonal, and so independent of all other dimensions. For example, the three spatial dimensions, XYZ, are entirely independent of each other. A domain is a sphere of knowledge that contains all possible values for the attribute being analyzed. There can be an expression of one domain in another. Examples are the time and frequency domains. An electrical signal may be viewed as amplitude over time or an amplitude over frequency. Both representations are useful for different purposes but each is preferable for the kind of analysis that suits it best. Using the right domain makes an analysis easier and more accurate. Using the wrong domain makes the analysis more difficult and prone to error. For the question of comparing AI to human performance, we want to make sure we have a full set of dimensions to contain the essential nature of human beings and also do our analysis in the domain that is most conducive to getting an accurate result for the characteristic being analyzed.

We know humans exist in the three spatial dimensions and in time, four dimensions, but do those dimensions fully define a human? Do humans exist in dimensions that reach beyond these four?

In the analysis of imaging blood flow in the human body, we introduced the domain that contains the direction of blood flow over time. Are there other defining domains? We know that electrical pulses are integral to the function of the human brain. Those electrical pulses operate in the frequency domain, which every radio engineer well knows. Further, we know that to fully describe those electrical pulses, we must described them as having a real part and an imaginary part. To describe the electrical function of the brain requires us to include both the real and imaginary parts of those electrical pulses. These new dimensions are necessary to describe the electrical signals in the human brain. However, this says nothing about the information being transmitted by those pulses. We know that the electrical signaling will be similar for all people but the information being conveyed, the thoughts being created, are vastly different. To create a taxonomy of thoughts requires the use of an information domain, in which our thoughts exist. We conclude that describing the electrical function of the brain requires us to include the real and imaginary parts of those electrical impulses and also address some of their components in the frequency domain. We further find that the information being conveyed by those electrical pulses exists in an entirely different dimension.

The domain containing the information, thoughts, and concepts is far from unified. Those that have thought about it identify many differing categories and types. Once we separate the domain that contains the brain’s physical signal processing from the content being processed, we find that the content that our brains process resides in multiple domains. Thought processes have been variously categorized into 6, 12, or even 39 distinct types. There appear to be more dimensions to our thinking than there are to our physical existence.

People and the universe in which we exist contain far more than the three spatial dimensions plus time. There is a wide variety of dimensions and domains. To fully describe either a person or the universe requires us to include a number of these dimensions and domains.

It is clear that all of the universe, even within the four dimensions of space plus time, cannot be directly observed by our senses. Even what we can observe is transmitted to our brain as modified by the limitations and flaws of our sensory organs. Our brains get both a limited and distorted image of the universe. We use instruments and other techniques to learn about parts of the universe that we cannot directly observe. In some cases, we have yet to devise a way to observe certain parts of the universe. But we know of their existence and learn about them by the effect they have on parts of the universe we can observe.

A consequence of the limits and inaccuracies of our sensory organs is that our understanding of the universe must be accepted on faith. The important point is that our faith be guided by the right basis. I have often said that, as an engineer, I know that my instruments will look me straight in the eye and lie to me. What I mean by that is that you have to know your instruments. Once you get them down near their noise floor, they are just telling you what their noise floor is. You are not getting a true reading of the thing you want to measure. Similarly, once you get to the top of an instrument’s range, it will keep giving you readings but all you are really getting is the maximum reading of which it is capable. Beyond these range limits, all instruments have flaws that must be understood. Reading, to be accurate require adjustment to compensate for the characteristics of the instrument. Once we move away from only believing what our senses tell us, we enter the world of faith. We have to choose to believe our instruments. If we accept the string theory of modern physics, we choose to accept the math and rationale that justifies it. If we follow a particular religion, we are doing so based on faith in the canonical text or teacher of that religion. Using faith to inform our understanding of the universe is unavoidable. It is then of great importance that we be very careful in selecting where we place that faith.

Now let us consider the characteristics of this universe. Consider beauty. Beauty does not exist at a specific location and time. It is expressed in locations and at times but the beauty itself is not defined by XYZ coordinates plus time. We can contemplate attributes like love, kindness, and joy. None of these attributes can be quantified or directly measured. It is possible to live a life filled with love, beauty, kindness, and joy. It is also possible to live a lonely, ugly, life filled with despair and despondency. It may be impossible to quantify the difference, but we know that the difference is very real. The attributes are real and impact us greatly, but they exist in their own domain, outside the four dimensions of what is sometimes called the real universe.

Beyond attributes there are values. What makes one thing worse than another? If people can be replaced by machines, what makes the replacement either good or bad? Our values guide our choices, but values are neither sensible nor quantifiable. Without values this question, along with many others, becomes meaningless.

If the universe extends well beyond the directly sensible universe to include attributes and values, does it go so far as to include the spiritual? We might start by asking what the ultimate cause is for existence? At the starting point, what brought the universe into being and determines what happens in it? Is that ultimate First Cause intelligent (God) or unintelligent (chance)? Creations reflect the characteristics of their creator. By this logic, most would agree that the universe is not random; there is an order to it. This suggests that the First Cause is not random. The universe evidences a design, suggesting an intelligent designer. We can then ask where that intelligent designer of the universe exists? The intelligent designer of the universe cannot exist within the universe because then the cause would be inside the effect. The creator must be outside the creation. Even if one chooses to believe that the universe is the product of random chance, where does random chance exist? It must be outside the thing acted on. There must be an existence that is outside creation. We can call this world the spiritual realm. It is the realm in which the creator exists and from which the creation is derived.

We can conclude that the universe extends far beyond what is directly sensible. The universe includes components that can only be perceived by using instruments or by their effects on things that our senses can observe. More than these, our universe includes attributes such as order and beauty. Temporally, it has a past and future, which are real but not directly observable. Finally, it must have a point of origin, a First Cause that is outside of it. There must be dimensions beyond space and time; physics, religion and logic all agree on this. There is the dimension in which the First Cause exists. In addition, there are the domains of attributes and other realities that may have expression in the universe but exist outside of it.

In the next article in this series, we will turn our attention to mankind. In this complex, multi-dimensioned universe, what are the dimensions and domains required to fully describe a person? Once we understand that, we can decide what aspects of human performance we should compare AI performance to. Getting the domain of comparison right will be critical to accurately answering the question, can AI machines ever fully replace people?